Picking the Right Investment

Between 1980 and 2000 just about everything that could go right for equity investors went right. Since 2000, just about everything that could go wrong has gone wrong. Going forward, the question is; how can a standard investment portfolio predominantly consisting of equities and bonds be improved? What kind of assets will perform well in the current and future economic environment, and should therefore form a part of any portfolio?

1980 – 2000: Perfect Equity Environment

If one had invested in the US equity market in the late 1970s and held that investment for the subsequent twenty years, that investor would have seen a return on investment of 12.8% per annum. The returns on the UK equity market were about the same. But what exactly made equity investment so attractive during this period?

In the late 1970s, to fight inflation bond, yields started at a generational high. For the next twenty years, as central banks took more and more control of inflation moderation, bond yields dropped consistently, making the investment environment for equities increasingly interesting.

Labour markets were de-unionised and became subsequently more flexible. Global outsourcing provided an almost unending supply of effective and cheap global labour, unemployment fell, productivity increased and demographics were supportive. In addition to that oil and most raw materials were cheap, and household and government borrowing was generally low. As a result, investors saw fantastic returns from equities over this period and the“buy-the-dip” mentality became a legitimised investment technique.

Since the turn of the Millennium

Over the past twenty years, central banks have consistently lowered interest rates at the merest hint of weaker growth. Governments and households were encouraged to borrow more and more and a mentality of spending today what one might earn tomorrow became commonplace. Now interest rates are at almost zero, governmental debt is spiralling out of control and the further stimulus of reducing interest rates even further is not an option any more.

In this situation, in order to boost growth governments and central banks turned to the unconventional monetary policy in the shape of quantitative easing.

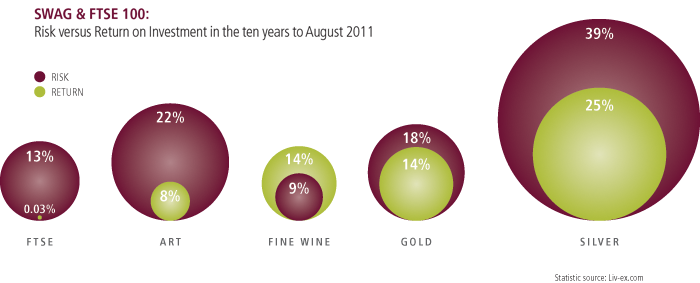

Given this backdrop, it is perhaps unsurprising that investors have been looking to other areas for better returns. Property has naturally soaked up a large portion of this demand (though of late this is a dangerous area itself) with some investors favouring precious metals, art, classic cars and of course, investment wine.

Following the classic vintage in 2014, there has been an extraordinary run of form with classic, very good or excellent vintages back to back – which is unprecedented. In 2015, we were rewarded with a very good vintage, with prices creeping up from 2014. In 2016, this was arguably one of the finest vintages in a lifetime, with the critics giving top scores across the board. In 2017 – another very good year, similar in style to 2015. With 2018, another very well regarded year with scores just below 2016. Our concerns at this point were about the continuous rise in release price and the effect on the investment upside opportunity over time.

Following the classic vintage in 2014, there has been an extraordinary run of form with classic, very good or excellent vintages back to back – which is unprecedented. In 2015, we were rewarded with a very good vintage, with prices creeping up from 2014. In 2016, this was arguably one of the finest vintages in a lifetime, with the critics giving top scores across the board. In 2017 – another very good year, similar in style to 2015. With 2018, another very well regarded year with scores just below 2016. Our concerns at this point were about the continuous rise in release price and the effect on the investment upside opportunity over time.